The Myth of Fast Grass and Its Evolution

The Sacred Lawn: Grass as the Soul of Tennis

Grass is not simply a surface for tennis; it is its cradle, the very essence of "Lawn Tennis" as it was conceived in the 19th century. Historically, its intrinsic characteristics—a low, fast, and often unpredictable bounce—forged an aggressive style of play, rewarding powerful serves, precise volleys, and a fearless approach to the net.

The evolution of grass court speed reveals the existence of two distinctly separate eras. The first, covering the period from 1979 to 2000, represents the pinnacle of a "wild," rapid, and sometimes treacherous grass, which demanded extreme tactical and technical specialisation. The second era, from 2001 to the present day, is instead defined by a deliberate and systematic slowing down of the surfaces, particularly at Wimbledon, which has led to greater homogenisation of playing conditions and brought grass closer to the other surfaces on the tour.

Decoding "Speed": A Complex Interaction

The concept of "speed" in tennis is a complex construct, the result of a dynamic interaction between three fundamental elements. It is not a static property of the surface alone, but an emerging phenomenon that depends on:

The Surface: Its physical properties, such as the coefficient of friction and the coefficient of restitution, determine how the ball interacts with the ground, influencing the loss of horizontal speed and the height of the bounce.

The Equipment: The technological evolution of racquets and balls has transformed the game. Modern carbon fibre and graphite racquets and polyester strings allow players to generate levels of power and spin unimaginable in the wooden era.

The Player: Tactical strategies and stroke biomechanics have adapted in response to changes in the surface and equipment, with a growing emphasis on power from the baseline.

To quantify this complex interaction, several measurement systems have been developed. It is crucial to distinguish between the Court Pace Rating (CPR), a system standardised by the International Tennis Federation (ITF), and the Court Pace Index (CPI). The CPR is a laboratory measurement that classifies the intrinsic speed of a surface on a scale from 1 (Slow) to 5 (Fast), based on controlled tests that measure friction and bounce. The CPI, developed by Hawk-Eye, is instead a dynamic metric calculated during tournaments that measures the actual "playing conditions," taking into account variable factors such as the type of balls used, atmospheric conditions (humidity, temperature), and court wear. These are complemented by statistical indices like those from Tennis Abstract and Ultimate Tennis Statistics (UTS), which use real match data (e.g., ace percentage) to estimate the speed of play, offering a valuable historical perspective dating back to 1991.

The distinction between the potential speed of a surface (CPR) and the effective speed of play (CPI and statistical data) is fundamental. Often, players' complaints about "slow" courts clash with organisers' claims that the physical composition of the surface has not changed. This apparent contradiction is resolved by understanding that the player's perception is influenced by the overall speed of play, which depends on variables external to the surface itself, such as heavier balls or high humidity conditions. A comprehensive analysis must therefore consider both dimensions to decipher the evolution of speed on grass.

The Golden Age of Fast Grass (1979-2000): Hierarchy and Characteristics

Wimbledon: The Icon of Rapidity and Unpredictability

In the period between 1979 and 2000, Wimbledon was the undisputed temple of fast tennis. Its courts were composed of a mixture of 70% perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) and 30% red fescue (Festuca rubra). This composition, less dense and durable than the current one, wore out quickly, especially along the baseline. The result was a surface that produced extremely low, fast, and, above all, irregular bounces. The ball did not bounce, it "skidded" away, making baseline play an arduous and often frustrating endeavour. This tactical context imposed an almost obligatory choice: the serve-and-volley. To win at Wimbledon, it was necessary to dominate with the serve and approach the net to finish the point before an abnormal bounce could compromise the rally. Players like John McEnroe, Boris Becker, Stefan Edberg, and Pete Sampras, masters of the attacking game and gifted with exceptional volleys, defined this era, transforming the serve-and-volley from a tactical option into a strategic necessity. The quantitative data available for the end of this period confirm this perception: the Ultimate Tennis Statistics (UTS) speed index for the 1991-99 decade gives Wimbledon an average value of 53.4, clearly positioning it as the fastest among the four Grand Slam tournaments.

The Australian Anomaly: The Kooyong Courts (until 1987)

The grass of the Australian Open, hosted at the Kooyong Lawn Tennis Club until 1987, was not a simple replica of Wimbledon's. Its unique characteristics made it an almost hybrid surface, which altered the traditional dynamics of grass-court play. The testimonies of players from that era are illuminating. John McEnroe noted that the courts had a slope to aid drainage, effectively forcing players attacking the net to run slightly "uphill". Pat Cash, one of the greatest grass-court specialists of his generation, described Kooyong as "much more favourable to baseliners" due to a "much higher bounce" compared to Wimbledon.

This peculiarity was likely due to a harder and more compact subsoil, a necessity dictated by the hot and dry Australian climate, which increased the surface's coefficient of restitution (COR). A higher, more regular bounce neutralised the main advantage of attacking players—the low, skidding ball—and granted baseliners the necessary time to set up their powerful shots. This "Kooyong paradox" explains the success of players like Mats Wilander, a master of the baseline game who won two titles in Melbourne (1983, 1984) but never managed to get past the quarter-finals at Wimbledon. Similarly, Chris Evert's victory over Martina Navratilova in the 1982 final, achieved despite a clear technological disadvantage in racquets, demonstrates how the conditions at Kooyong levelled the playing field, reducing the gap between different styles.

A Rich and Varied Ecosystem: The Other Grass Tournaments

The 1979-2000 era was not defined by the Grand Slams alone. There was a rich and varied grass-court circuit that constituted a substantial and significant part of the tennis calendar. In Australia, besides Kooyong, grass tournaments were held in Sydney (at the White City Stadium), Adelaide (Memorial Drive), and Brisbane (Queensland Open). In the United States, the US Open had been played on grass until 1974, and prestigious tournaments like the U.S. Pro Championships at the Longwood Cricket Club and the Newport Casino Invitational were key stops on the circuit. In Europe, the Queen's Club in London and the Manchester tournament were renowned for their extremely fast surfaces, considered by some players to be even quicker than Wimbledon in the early stages of the tournament.

However, this ecosystem has undergone a drastic downsizing, mainly for economic and logistical reasons. The maintenance of a professional-level grass court is a complex, expensive operation that requires specialist skills throughout the year, unlike hard or clay courts which have significantly lower management costs. With the globalisation of tennis and the standardisation of the ATP and WTA calendars, tournaments have favoured low-cost surfaces. The short time window between the Roland Garros and Wimbledon has made it economically unsustainable for many organisers, especially outside of Europe, to maintain expensive grass facilities for such limited use. This has led to the almost total disappearance of grass tournaments in North America and Australia, concentrating the season almost exclusively in the United Kingdom and a few countries in continental Europe.

Hierarchy of Speed (1979-2000): A Qualitative Ranking

The New Millennium Revolution (Post-2000): Slowdown and Homogenisation

The Turning Point: Wimbledon 2001 and the Perennial Ryegrass

The watershed moment in the modern evolution of grass courts is universally identified as 2001, when the All England Club made the historic decision to change the composition of its lawns, switching from a mixture of ryegrass and fescue to a turf composed of 100% perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). This choice was not accidental but the culmination of an agronomic strategy aimed at making the courts more resistant to the wear and tear of modern tennis, which was becoming increasingly physical and powerful. However, the consequences for the game were profound and immediate.

The slowing of Wimbledon is not a myth, but the result of a combination of scientifically guided factors:

Grass Composition: Perennial ryegrass is a more robust species that grows in denser, more vertical tufts than red fescue. This increased density of the turf increases friction (Coefficient of Friction - COF) upon impact, slowing the horizontal component of the ball's speed.

Soil Compaction: In parallel, maintenance techniques have become more sophisticated. Under the guidance of head groundsmen Eddie Seaward and, subsequently, Neil Stubley, the focus has been on creating a harder and drier subsoil. The use of heavy rollers and the constant measurement of hardness with tools like the "Clegg soil impact hammer" have led to a significantly more compact soil. A harder soil increases the Coefficient of Restitution (COR), generating a higher and, above all, more predictable bounce.

The combined effect of these two factors has been lethal for the traditional grass game. The increase in friction (slower ball) and the increase in bounce height (more time for the player) have transformed the dynamics of the game. The balls no longer "skid" low and fast, but "rise," creating a more comfortable trajectory for heavy topspin shots from the baseline. Besides durability, an unofficial but widely discussed motivation for this change was the desire to produce longer and more telegenic rallies, responding to specific commercial and entertainment demands.

The Modern Player's Arsenal

The impact of the courts slowing down has been amplified exponentially by the technological evolution of equipment. Modern racquets, made with composite materials like graphite, carbon fibre, and kevlar, are significantly lighter, more powerful, and more stable than the wooden and aluminium frames of the past. Even more decisive has been the introduction of polyester strings, which allow players to impart an amount of spin (topspin) and power on the ball that was previously unimaginable. This combination has turned baseline passing shots and service returns into lethal weapons, capable of neutralising the net attack even on traditionally faster surfaces. Furthermore, the ITF has introduced different types of balls (Type 1, 2, 3) to modulate the speed of play depending on the surface. Many players have complained that the Slazenger balls used at Wimbledon, while respecting the specifications, tend to become heavier and fluff up quickly, further contributing to slowing down the game and making it more difficult to hit outright winners.

The New Hierarchy of Speed (Post-2000)

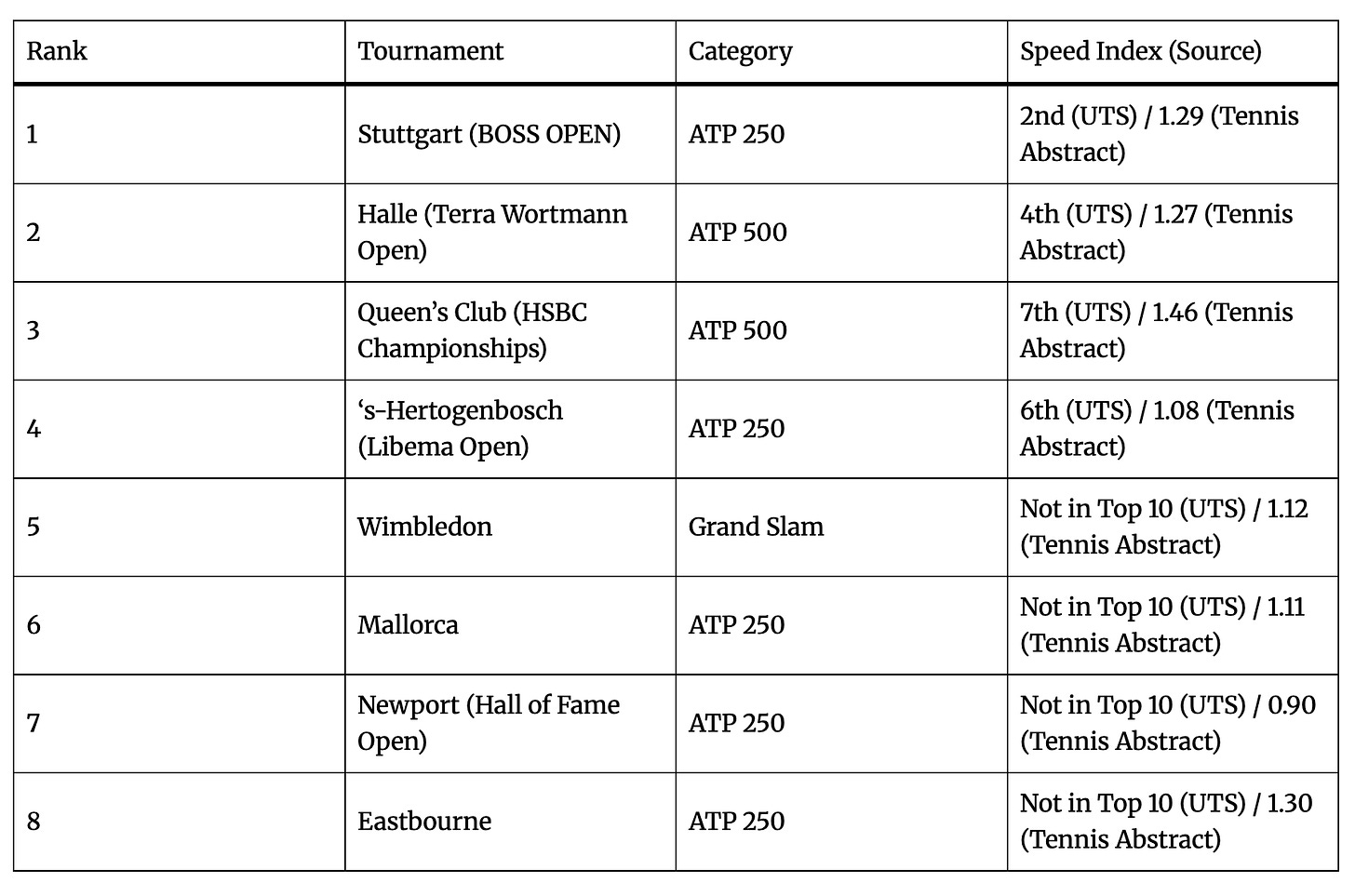

Contrary to common perception and its historical fame, modern data indicate that Wimbledon is no longer the fastest grass-court tournament on the ATP tour. Lower-category tournaments, such as the ATP 500s in Halle and at the Queen's Club, consistently record higher playing speeds. Rankings based on statistical metrics, such as those developed by Ultimate Tennis Statistics and Tennis Abstract, regularly place Halle, Queen's, and Stuttgart at the top for speed, often ahead of Wimbledon. A ranking published by tennisedge.io, based on the average of 2022 and 2023 data, places Halle third and the Queen's Club sixth in the overall speed ranking of all ATP tournaments, while Wimbledon is positioned only in seventeenth place.

This reversal of the historical hierarchy is likely due to a difference in maintenance objectives. Wimbledon, having to ensure the durability and consistency of the courts for two weeks of intense play with 128-player draws, adopts an agronomic approach that prioritises the resistance of the turf, even at the cost of slightly lower speed. Shorter, one-week tournaments with smaller draws can afford to prepare more delicate and faster surfaces, more akin to "old-style" grass, without the risk of excessive degradation before the final.

Note: The ranking is based on aggregated data and averages from several recent seasons (post-2021) from Ultimate Tennis Statistics and Tennis Abstract. The values may vary slightly from year to year.

Comparative Analysis and Technical Insights

Two Eras Compared: Wimbledon Before and After 2001

The change in the composition and maintenance of the Wimbledon courts post-2001 has produced a measurable and profound transformation in the style of play. Statistical analysis reveals a drastic reduction in the frequency of the serve-and-volley. Data collected by Craig O'Shannessy show that this tactic, used in almost a third of points (33%) in 2002, plummeted to less than 7% in 2018. This change is accompanied by an increase in the average rally length and a modification of point dynamics.

A critical analysis of quantitative speed data, however, reveals greater complexity. The data from Ultimate Tennis Statistics (UTS) show an increase in the numerical value for Wimbledon in the post-2001 period (from 53.4 in 1991-99 to 81.7 in 2010-19). This apparent contradiction is explained by the UTS methodology, which heavily weights serve effectiveness (aces, points won on serve). The increase in the value therefore reflects the evolution of taller, more powerful players with devastating serves thanks to racquet technology, rather than an intrinsic increase in the surface's speed. In contrast, the metrics from Tennis Abstract, which analyse the relative difference between surfaces, show a clear "convergence," indicating a relative slowing of grass compared to other surfaces over the years.

Note: The data on S&V and rally length are estimates based on qualitative analysis and partial data. The serve speed data are based on historical averages.

The Physics of the Bounce: COR, COF, and the Role of Grass

To fully understand the transformation of the game on grass, it is essential to analyse two key physical principles:

Coefficient of Friction (COF): This measure quantifies the loss of the ball's horizontal speed after the bounce. Grass has an intrinsically low COF, which causes the characteristic "skid" of the ball. The greater density of the post-2001 perennial ryegrass, compared to the previous mixture, has slightly increased the COF, helping to slow the ball down.

Coefficient of Restitution (COR): This measure defines the vertical elasticity of the bounce, i.e., how high the ball bounces. Grass has a naturally low COR because the soft soil absorbs much of the impact's energy. However, a harder, more compact soil, like that introduced at Wimbledon in the new millennium, significantly increases the COR, generating a higher bounce.

The most lethal change for the classic attacking game was not so much the modest reduction in horizontal speed, but the drastic increase in the height of the bounce. A higher bounce is the antithesis of an effective approach volley. The serve-and-volley tactic was founded on the ability to play a serve, often a slice, that stayed low and fast, forcing the opponent to hit the ball from low to high and produce a weaker return, ideal for being intercepted at the net. The switch to a more compact soil and a grass that promotes a higher bounce has destroyed this dynamic. The opponent has more time and can hit the ball in a more comfortable "strike zone," at hip height, generating powerful, topspin-laden passing shots that become unmanageable for the player at the net, whose first volley often turns into a very difficult half-volley from a retreated position.

Voices from the Court: The Testimonies of the Protagonists

The perceptions and analyses of the players, the true protagonists, offer an irreplaceable qualitative perspective that corroborates the technical and statistical data.

Roger Federer, despite being one of the greatest grass-court players of all time, has repeatedly expressed his disappointment with the general slowing of surfaces, arguing that faster courts would better reward attacking play and tactical variety.

The great serve-and-volley exponents of the previous era, such as Goran Ivanisevic, Pat Cash, and Tim Henman, have all commented critically on the slowing of Wimbledon, stressing how it has denatured the grass-court game they knew, making it more similar to that on other surfaces.

Martina Navratilova, the queen of Wimbledon with nine titles, has observed with great acumen that the difference between clay and grass has narrowed considerably. "The clay is playing faster... and the grass is playing slower," she stated, highlighting a clear convergence of the surfaces.

Jonas Bjorkman, a former top doubles player and excellent singles player, has expressed concern that this homogenisation is leading to the disappearance of tactical diversity, warning of the risk of having "only one type of player" capable of dominating on all surfaces.

These consistent testimonies, from different generations and playing styles, confirm that the change has not just been a matter of physical measurements, but has had a profound impact on the perception, strategy, and very soul of the game on grass.

A Lost Identity or a Necessary Evolution?

The analysis outlines a clear evolutionary trajectory for grass tennis courts, marked by a turning point at the beginning of the new millennium. The hierarchy of speed in the 1979-2000 era was dominated by a fast, unpredictable grass that required deep tactical specialisation. Wimbledon and the Queen's Club represented the pinnacle of pure speed, while the Australian Open courts at Kooyong constituted a fascinating variant, a "slower" grass with a higher bounce that mitigated the absolute dominance of the serve-and-volley.

The post-2000 era has seen a reversal of this hierarchy. Wimbledon, in a context of globally slower play, has ceded the top spot for speed to one-week tournaments like Halle and Queen's. This transformation was not accidental but the result of a strategic and deliberate decision, driven on one hand by specific agronomic needs (the switch to 100% perennial ryegrass for greater durability) and on the other by commercial pressures (the search for longer, more telegenic rallies). The impact of this choice has been amplified by an unprecedented technological evolution in racquets and strings, which has provided baseliners with an arsenal capable of neutralising the net attack.

Final Reflections: The Future of Grass in Modern Tennis

The evolution of grass courts raises a central dilemma for modern tennis: the balance between preserving the diversity of surfaces, which has historically rewarded different playing styles and made winning the Grand Slam a true test of completeness, and the commercial and television pressures pushing towards homogenisation to ensure a more standardised and, presumably, more spectacular product for the general public.

Has grass lost its "treacherous" and unpredictable identity, becoming, as some have called it, a "green clay court"? Or has it simply evolved to remain relevant and playable in an era of hyper-athletic tennis dominated by baseline power? The answer probably lies somewhere in between. While it is undeniable that systematic serve-and-volley has disappeared and rallies have become longer, it is also true that grass remains a unique surface. It still requires specific adaptations in movement, a lower centre of gravity, a preference for flatter shots, and a greater emphasis on the first shot of the rally (serve and return). Although slower and more predictable than in the past, grass has not yet become a hard court. Its living, changing nature, the sensation of sliding, and the still relatively low bounce continue to make it a unique challenge. The grass season, however brief, remains a fascinating and distinctive chapter of the professional tour, a test of adaptability that, despite having changed its rules of engagement, has not entirely lost its soul.